Laser Measurements 101

Part 5: Measuring The Unmeasurable

The final piece of our measurement puzzle is to measure the \(\Delta n\) while we are changing our laser’s wavelength. As discussed in Part 4, we can change the current to change the wavelength, but that only helps us if we can measure the \(\Delta n\). If we can measure \(\Delta n\), we know that will be a linear function of the true distance. We also remember from Part 2 that we can measure frequency difference between the transmitted and reflected wave by measuring the current of a photodiode on the back side of the laser. Let’s combine all of this knowledge into a simple algorithm for doing our distance measurement!

Remember from Part 2 that our photodiode will measure the combined waves. This will be a standing wave like the black wave you see shown here. As you can see, for every 1 wavelength of relative wave motion, we will see a full oscillation of the standing wave from positive -> negative -> back to positive again.

In short, we will measure the \(\Delta n\) simply by counting these events. The rest of this article will explain the details of how this can be done.

First, remember what the photodiode (PD in the diagram) is actually measuring; the intensity of the combined light source. So what would it mean for our combined standing wave to be negative, would that be less than 0 light??

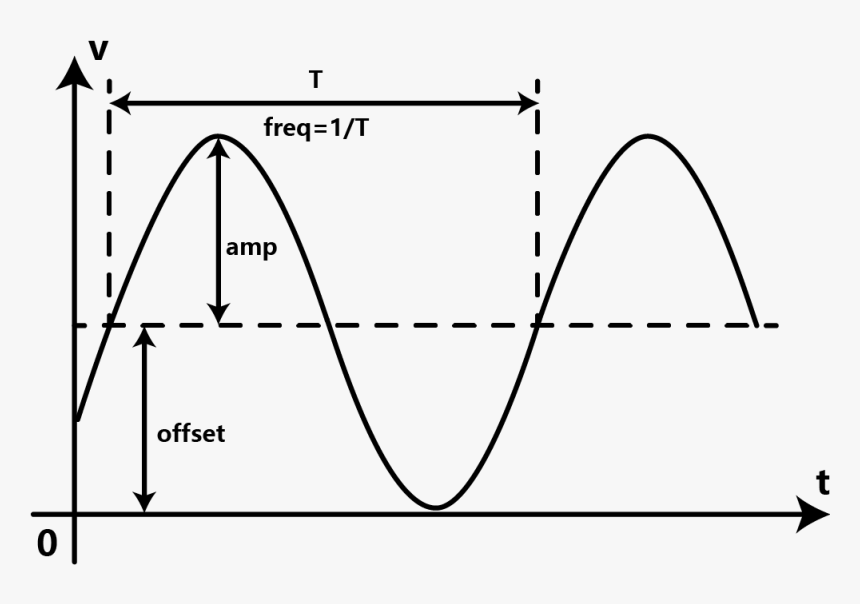

Intuitively, the light will oscillate, but it will do so around the nominal light intensity value of the laser. In electrical engineering terms, it has a DC offset

This DC offset value will represent the brightness of the ambient light, the laser light, and any other light source hitting the sensor. Those parameters will set the offset value of the sine wave that we will be measuring.

However, the frequency of the wave will be set by the variation of wavelength in the laser as we modulate the current.

This yields the obvious question; if the offset is set by the ambient brightness, then what determines the amplitude of the sine wave?

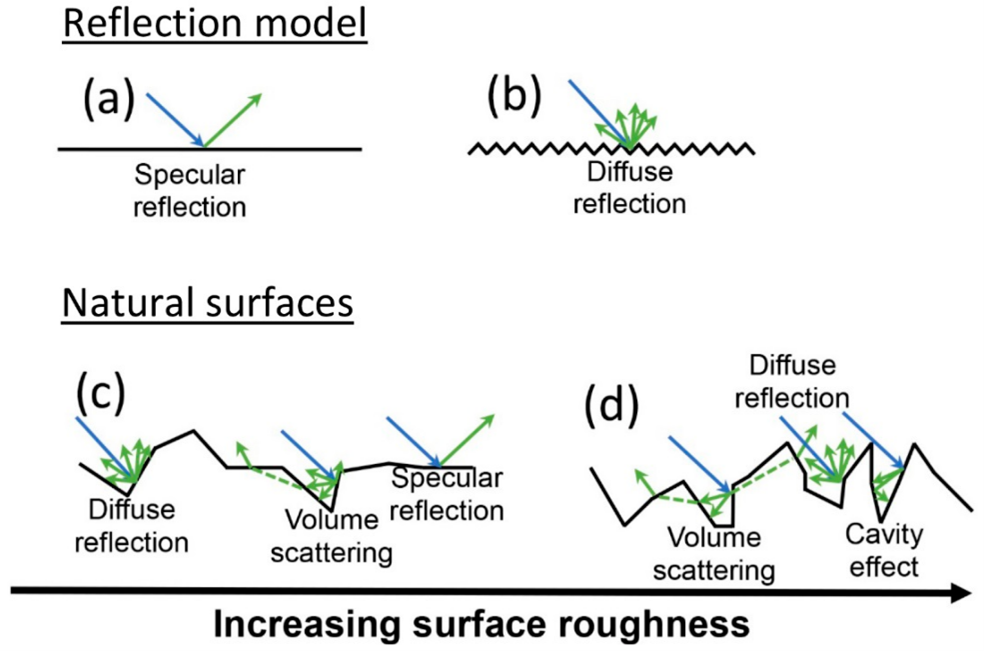

Remember we discussed that most of the light will be scattered diffusely, but some small portion will return to the source? The amplitude is set by how much of that light comes back. In other words, though we’ve been drawing the amplitudes of the transmitted and returned light as identical, the transmitted light is >100x stronger than the reflection!

In the technical literature, this is called the optical coupling factor. As the name implies, there is optical coupling between the target of the laser, and the laser itself. In effect, they become one giant laser, where the target “mirror” is simply much less efficient (<1% of the light is reflected) than the original laser cavity.

We will ignore the optical coupling factor for our purposes, just understand that this is derived from the materials and geometry, and it limits our ability to measure as the distance (among other factors) grows.

There are some subtleties I am intentionally ignoring around the exact shape of the wave. In the upcoming “Laser Measurements 102” series, we will discuss more details around optical coupling, the reason the reflection causes a phase shift (spoiler: Maxwell’s equations), and much more! For now, we can simplify this system down to the idea that our photodiode will measure a large voltage with a very tiny half-sine wave hidden inside of it!

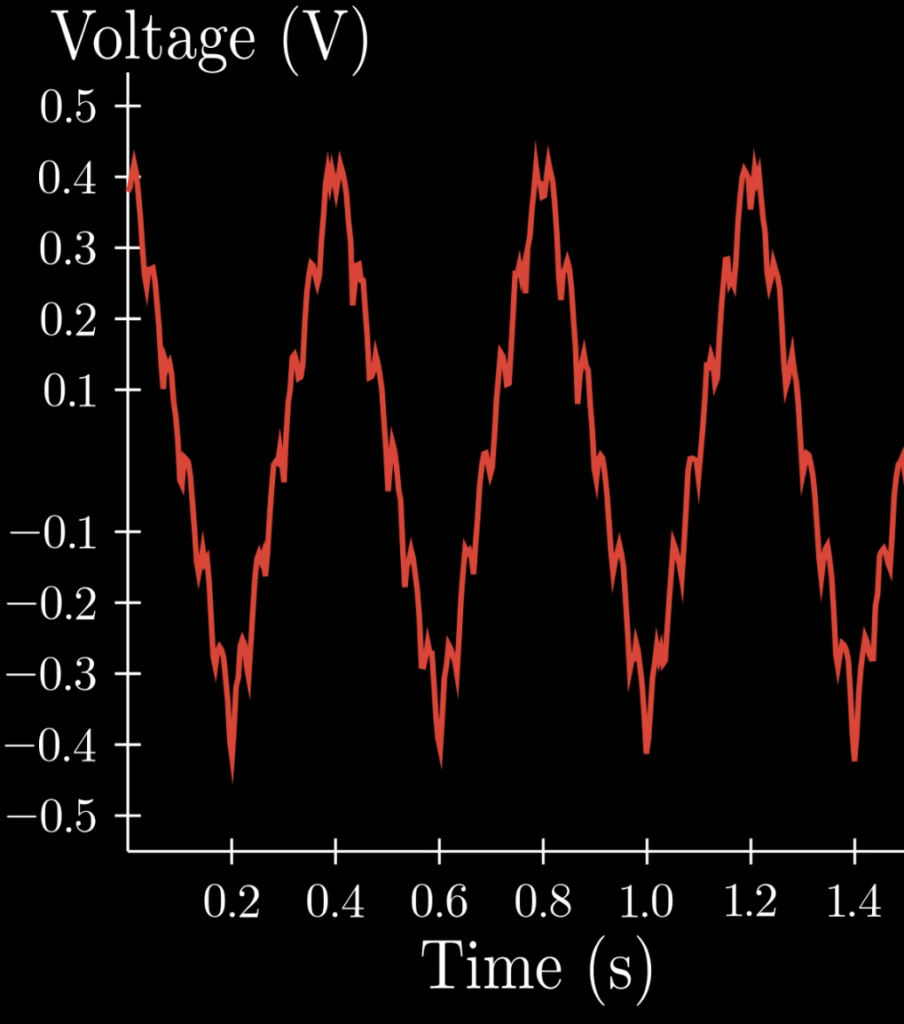

Once accounting for the optical coupling and the noise in the measurement, the photodiode voltage (converted from current using a TIA) will look something like the illustration shown here. (I have added some noise to the signal to make it a bit more realistic – no measurement is ever noise free!)

Take the X and Y axis units with a grain of salt. As mentioned, the DC voltage will vary depending on the laser strength (in addition to the amplifier calibration), and the time scale will depend on the distance being measured, the laser wavelength, and the shape of the modulation current being used to modify the wavelength.

In reality, for most practical setups, the time axis would be in milliseconds (or even \(\mu s\)!).

There is one more step we must add: remember that we need a wavelength change to measure distance! And that wavelength change will be caused by changing the current. The \(\Delta n\) we are going to use to measure distance is the difference in the number of period between those two wavelengths.

The plan is to ramp linearly from the lower laser current to the higher laser current. This will induce a predictable linear change in laser wavelength. We can count the \(\Delta n\) during this ramp, and that will give us our distance measurement!

Of course, once we arrive at the higher current, we need to return to the original lower current, so we will return back down in the same linear fashion. This is handy, we can take another measurement on the way down!

In the illustration shown here you can see what this will look like after canceling the DC voltage, and with a realistic amount of noise added. You can see each phase jump overlayed on the triangle wave shape. All we need to do is to measure these jumps to get distance!

To get a full algorithm, we do need to somehow count these jumps in our signal. This is possible to do by taking a derivative, although the noise can make that a very unreliable strategy! A cleaner option is to run the signal through an FFT!

This will show all the relevant frequencies, and usually the highest one will be the one we are interested in!

You might be wondering “but we want the number of changes in period \(\Delta n\), not the rate of change over time \(\frac{d \Delta n}{dt}\) which the FFT will give us”. This is true, but once again, we can rely on the calibration to save us. We will assume that the time to ramp up and ramp down are equal, and do not change for each sample we collect! Therefore the time element is a scaling factor which the calibration will account for!

Note that with a non-moving target, we can relay on the ramps up and ramps down having the same frequency. But if the target has velocity, the two ramps will have different frequencies, and we will need to measure them independently!

If you want a more visual breakdown on how this works, there are some highly clarifying animations in the video linked at the end of this blog!

We have now created a way to measure the velocity of a target using an unmodulated (constant power) laser. We have also created a way to measure the distance of a target using a modulated (triangle wave power profile) laser! Next time, we will discuss how we can measure both the velocity and distance of a target simultaneously, and explain how they are truly independent measurements from each other!